Notes on Spinoza

- Spinoza’s relationship with the medieval philosophers

- Nadler on Spinoza

- Maimonides and Spinoza

- Spinoza and Averroes

- from Maimonides to Spinoza

- The Maimonidean origin of Deus sive Natura

Spinoza’s relationship with the medieval philosophers

Spinoza has been described as ‘the last of the medievals and the first of the moderns’.

Harry A. Wolfson, The Philosophy of Spinoza Vol.I Chapter 1 pg 20:

[His philosophy] has grown out of the very philosophy which he discards, and this by his relentless driving of its own internal criticism of itself to its ultimate logical conclusion.

Spinoza Ethics I.29:

Nothing in the universe is contingent, but all things are conditioned to exist and operate in a particular manner by the necessity of the divine nature.

Nadler on Spinoza

Steven Nadler, A Book Forged in Hell: Spinoza’s Scandalous Treatise and the Birth of the Secular Age, Chapter 4 p.65:

In the Treatise, Spinoza is deeply concerned to combat this notion of the prophet-philosopher [i.e., Maimonides’ theory of prophecy]. One of the goals of the work is to secure the separation of the domains of religion and philosophy so that philosophers might be free to pursue secular wisdom unimpeded by ecclesiastic authority.

Steven Nadler, Why Spinoza Still Matters:

Spinoza is often labelled a ‘pantheist’, but ‘atheist’ is a more appropriate term.

Steven Nadler, A Book Forged in Hell: Spinoza’s Scandalous Treatise and the Birth of the Secular Age, Chapter 3 p.50:

Spinoza was always deeply offended by the accusation that he was an atheist, particularly if the charge meant, as his Voorburg opponents claimed, that he “mocks all religions.” … Spinoza writes, “Does that man, pray, renounce all religion who declares that God must be acknowledged as the highest good, and that he must be loved as such in a free spirit? And that in this alone does our supreme happiness and our highest freedom consist?”

Maimonides and Spinoza

Maimonides departs from Aristotle on the question of the eternity of the Universe, but this is related to (and perhaps anciliary to) the question whether the Universe is entirely governed by natural laws. In the Guide II.20, Maimonides says

For as it is impossible to reconcile two opposites, so it is impossible to reconcile the two theories, that of [1] necessary existence by causality, and [2] that of Creation by the desire and will of a Creator

Maimonides emphatically rejects [1] and supports [2]. Spinoza, who had access to the Keplerian hypothesis and therefore no longer saw the same deficiencies that Maimonides did in the Aristotelian system, asserted [1] in Ethics I.29 and denied [2] in Ethics 1.17 sch. In doing so, he takes the opposite position to Maimonides while staying true to the latter’s philosophical framework.

Spinoza and Averroes

According to Carlos Fraenkel (in Spinoza on Philosophy and Religion: The Averroistic Sources, book chapter in The Rationalists: Between Tradition and Innovation) points out that the expression ‘truth does not contradict truth’ was used by Spinoza in Cogitata Metaphysica (as ‘veritas veritati non repugnat’). This phrase, of course, has a pedigree in Averroes’ Decisive Treatise where he uses it in the form (الحق لا يضاد الحق) al-haqq la yuzad al-haq. For Averroes, this statement is a lead-in to an allegorical interpretation of those parts of Scripture or religious tradition which contradict with philosophical truth. According to Fraenkel, Spinoza too held such a view at one point, although it seems very different from the position that Spinoza ultimately takes in the Tractatus Theologico-Politicus.

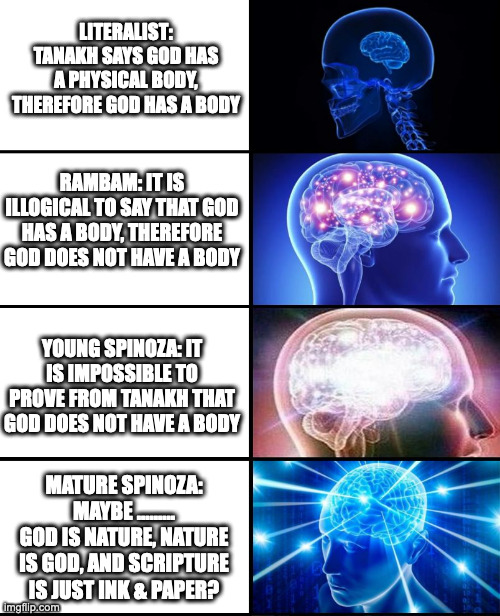

Fraenkel’s argument is that Spinoza follows Averroes rather than Maimonides in his ‘resolution’ of the conflict between ‘Jerusalem and Athens’. Averroes’ position is that the inner, allegorical meaning is the ‘true meaning’ of Scripture, but this is not accessible to the multitude because it takes philosophical reasoning to understand, from first princriples, why one should lead a virtuous life. So, religion is a kind of ‘short cut’ to the virtuous life for the multitude. Fraenkel believes that “an Averroist would not attempt to resolve contradictions between philosophy and theology by composing an allegorical commentary on problematic passages in scripture as Maimonides did, for instance, with Biblical anthropomorphisms”. (1) There is no need to do this because the multitude can continue to follow the literal meaning of Scripture with no harm to them, and (2) this could be dangerous because if people’s belief in the literal sense of religion is destroyed, and if they do not have the philosophical capacity to arrive at correct opinions about how to live purely by way of reason, then they would be left with no guide. Fraenkel references Averroes’ dictum that

The philosopher is prohibited from intervening in the beliefs of popular religion even if they are philosophically as untenable as the anthropomorphic representation of God. … [According to Averroes], philosophical doctrines may only be recorded in books that employ scientific demonstrations. For these, according to Averroes, are protected by their difficulty: books which “use demonstrations are accessible only to those who understand demonstrations” (Faṣl al-maqâl, 21). This, of course, is as true for Spinoza’s Ethics, 450 years later, as it is for Averroes’ commentaries on Aristotle.

from Maimonides to Spinoza

- Maimonides believes that the question of whether the world is eternal or created-in-time is not conclusively settled by philosophical speculation, and that from purely rational arguments we are forced to conclude (based on the scientific evidence available in the 12th century) that we do not know which one is true.

- Nevertheless, he chooses to believe in creation-in-time “on the authority of Our Teacher Moses”.

- He expressly says that his reason for this decision is not that a literal reading of Genesis tells us that God created the world at a certain instance of time, famously asserting that he would have had no trouble with interpreting the Genesis narrative allegorically had the scientific evidence for an eternal universe been conclusive.

- Nevertheless, he says that believing in creation-in-time is extremely important, and that the theory of the eternity of the world is “contrary to the fundamental principles of our religion”. Why?

- If one accepts creation-in-time, then miracles and prophecy also become possible. He does not directly state the converse, but we can conjecture: if creation-in-time were conclusively disproven, would miracles and prophecy become impossible?

- Creation-in-time has a bearing on the question of whether the entirety of Nature is subject to fixed laws, or whether there is a supra-natural power of God which shaped the Universe, at least in the early days? This question is so important to Maimonides that he stakes the entirety of the law on it. “If Aristotle had a proof for his theory … then we should be forced to other opinions”.

- He believes that there is no difference between (1) believing in an a Universe which proceeds from God the way all effects proceed from their causes and (2) believing that the Universe is the result of a voluntary act of the design/will/determination of God, but it has always been so.

The Maimonidean origin of Deus sive Natura

GP.III.32 begins with “On considering the Divine acts, or the processes of Nature, we get an insight into…”. The Arabic goes “إذا تاملت الأفعال الإلهي أعني الأفعال الطبيعية”. It has been speculated by none less than Shlomo Pines that this expression of Maimonides may have suggested to Spinoza the famous formula tion Deus sive Natura. There is certainly a linguistic parallelism, if we ignore for a moment that Maimonides talks about actions whereas Spinoza does not restrict his sive to the actions of God or nature.

- Maimonides says “الأفعال الإلهي, أعني, الأفعال الطبيعية”: “the actions of God, that is, the actions of Nature”

- Spinoza says “God, sive, Nature”

It might be instructive to look into the sort of equivalence set up by the Arabic أعني and the sort of equivalence set up by the Latin sive.

But in at least two of the three places in the Ethics where Spinoza uses this phrase, his argument never strays too far from Maimonides’ circumscribed equivalence of the actions of God with the actions of Nature. Consider the preface to Part IV of the Ethics in Elwes’ translation:

Now we showed in the Appendix to Part I., that Nature does not work with an end in view. For the eternal and infinite Being, which we call God or Nature, acts by the same necessity as that whereby it exists.

Although Maimonides differs from Spinoza in the conclusion which is stated here (for Maimonides, God does not act by necessity but has free will), notice that the two preceding premises are entirely shared between them.

- “Nature does not work with an end in view”. This is an opinion which was strongly held by Maimonides, and in Part III …

- the actions of God and the actions of Nature are one and the same. This was stated explicitly by Maimonides in GP.III.32.